Art and the Indian Act: 30 years of Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun

By Kelsey Klassen

Ask Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun about his art, and he’ll tell you about the Indian Act. Ask him again, and he’ll tell you about land claims, logging moratoriums, water rights, oil spills, residential school abuses, and Canada’s missing and murdered women. Ask him for his feelings on that subject, and he’ll tell you about his daughters, and how he feared for their lives under Stephen Harper’s rule.

In conversation and, most notably, on canvas, the acclaimed First Nations painter lays bare the challenges facing indigenous people today. Quite tellingly, they are also similar, if not identical, to the issues his community was grappling with when he first started his career, more than 30 years ago. Meanwhile, the ideas he puts forward reflect conversations Canadians are just now starting to have, from the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission findings to the spectre of climate change, as a whole about their shared environment and history.

Recognizing his place as one of Canada’s most significant contemporary artists, curators Karen Duffek, of the Museum of Anthropology, and Secwepemc artist Tania Willard, have brought together 60 of Yuxweluptun’s most confrontational and prescient works under the banner of Unceded Territories, a politically-charged yet playful overview of his oeuvre, running May 10-Oct. 16 at MOA.

On the cusp of this, his largest Canadian solo-show in 20 years, Yuxweluptun remains as polemic as ever. Seated in his studio in a paint-spattered leather chair, as his shaggy dog, Rez, happily chews a paintbrush at his feet, Yuxweluptun launches into a list, complete with dates and names, of the most egregious colonial injustices of the past 200 years, while taking every on-the-record opportunity to tell the politicians of British Columbia to fuck off.

Behind him, the newest piece for his show sits almost finished. It isn’t until the end of the wide-ranging, hour-long interview, however, that he even acknowledges it – a richly-hued, 18×11-foot rendering of a spirit dancer transforming into a wolf in a longhouse, surrounded by fire, smoke, drummers and spirit guardians. Through the doors of the wooden structure, one can just make out the rolling lines of one of Yuxweluptun’s iconic landscapes in miniature, drawing his connection with nature into the sacred space.

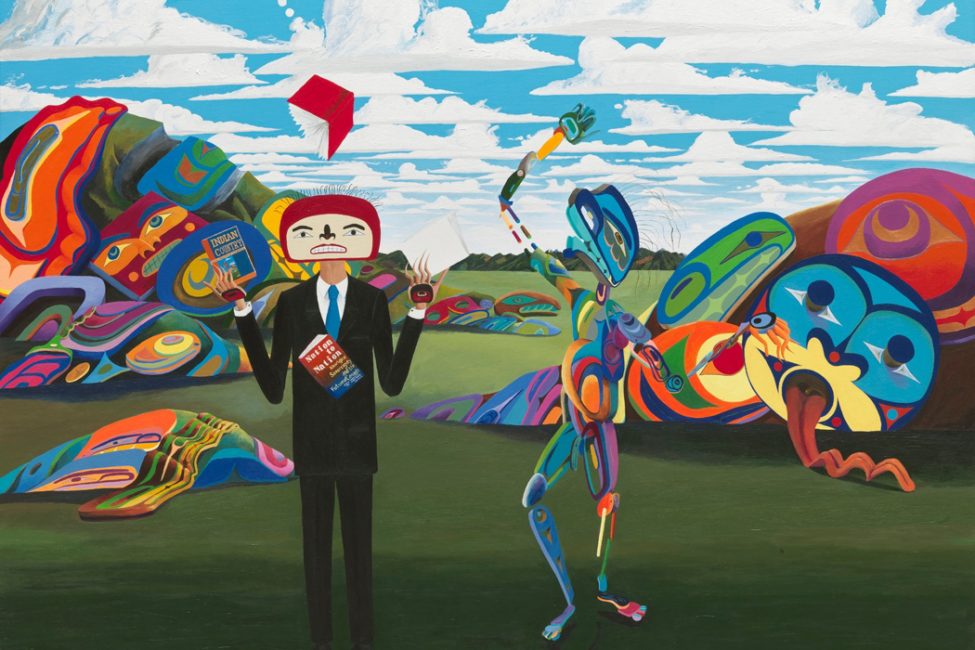

Joining this piece in the contemporary gallery at MOA are thought-provoking works like his 1990 Dali-esque ozone-crisis exposé, Red Man Watching White Man Trying to Fix Hole in the Sky; an excerpt from his 1997 installation, An Indian Shooting the Indian Act; and his recent boardroom- and back room-skewering Super-Predator series, as well as brand-new works yet to be seen publicly.

“Sometimes I consider myself a history painter,” Yuxweluptun says, of his groundbreaking subject matter. “I have to go back and record history, backtracking history, because if you only allow the colonialists to write history, what is really true?”

As he says this, and bears witness to countless examples of colonial suppression from his childhood to now, his resentment hangs as palpably in the air as it does on the gallery wall. Yuxweluptun is a master at raising eyebrows, however, this time by calmly dismissing the idea that he might, in fact, be angry.

“It’s not anger. It’s a natural part of an Indian being in this country,” he explains, before launching into a soliloquy on why Canada’s long-standing Indian Act should be renamed the White Supremacy Act. “I accept that Canadians treated us like shit. I accept the attitude of Canadians that are racist. They had to shut down the CBC comments because of all the racism that was written there. That’s basically […] par for the course of this country.

“Harper said that native women were not on his radar, for all the missing and murdered women,” he continues, as an example, “and we had to sit through that government. That’s like saying, ‘Let’s put a target on every native woman in this country.’ Because he [didn’t] – and Canadians don’t – give a flying fuck. They elected him,” he adds, heat creeping into his voice, “and it’s okay to go out and kill native women. I had to wake up to that every day, because I have six daughters, and I’m going, ‘Wow, you guys are a bunch of really fucking assholes.’ […] I’m supposed to have Truth and Reconciliation after this?”

Yet he largely paints for a non-aboriginal audience – using modernist art, he says, to subvert what an “Indian” is allowed to talk about.

Born in Kamloops in 1957, Yuxweluptun (a Salish name meaning “man of many masks”) found his way to social activism at the side of his Coast Salish father and Okanagan mother. Both highly involved within native organizations – his father was founder of the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs and his mother was executive director of BC’s Indian Homemakers Association – Yuxweluptun remembers travelling with his father to meetings from Chilliwack to Williams Lake, listening to his elders debate issues such as land claims, fishing rights, and human rights.

Having attended the Kamloops Indian Residential School for a time, before being granted the right to attend public school, Yuxweluptun also saw firsthand the devastation wrought by the residential school system, which he immortalized in his 2005 acrylic, Portrait of a Residential School Child.

“The difference between public school and residential school is really clear. You know what that is?” he asks, brashly. “There’s a graveyard in the playground outside. There was graveyards at the residential schools and they buried you there.”

One might wonder then, why Yuxweluptun would agree to the hosting of this show at a museum of anthropology – a collection house (he calls them “morgues”) like many others, with its own degree of colonial legacy. In response, Yuxweluptun, whose work has sparked conversation from the boardrooms of oil companies to the walls of the National Gallery of Canada, half-jokingly implies that MOA was the only institution that would have him.

Kidding aside, though, the museum is one of the few places where his work can sit in dialogue with belongings from the Pacific Northwest. And the Emily Carr graduate adds that, as an aboriginal modernist, doors like this weren’t always open to him when he first began.

“I didn’t get an offer to an artist-run centre until after I was at the National Gallery of Canada,” he says, as an example. “The art world is very much standard. It has its 72-per-cent male, white, Caucasian art, Canadiana policy, and the rest we’ll give it to the minorities. But you’ve got to be good at it,” he allows, after all these years. “The world of art is a gladiator’s arena of talent, and if you want to play in the world of art, there’s no rules. There’s no rules that say just because you think you’re good, you’re going to get there. It’s not true. You have to work twice as hard and be very good at it.”

More with LPY:

On getting established after art school:

As an artist, I had sketchbooks that were filled but I didn’t have the space, I didn’t have the studio, and I didn’t have some of the skills to pull off some of the paintings. But I figured that, if I keep doing what I’m doing the ideas and concepts will keep breathing and I’ll be able to catch up to some of them – the work that I wanted to do.

On the Indian Act:

This is the problem about Canadians; they’re polite about their racism. They just word it different so it sounds good to the rest of the world, but what we’re doing is just fucking the Indians, the aboriginal people, over.

On Stephen Harper:

He’s made natives very leery of Canadians. I think that he was so right-wing. [Although], I always say that there’s no such thing as a left-wing government in this country, when you’re dealing with aboriginal people.

On being a ‘landscape’ painter:

You’re trying to solve the solutions of the world, when you’re still looking at band politics, versus municipal politics, provincial politics, federal politics. Then you’re looking at Crown land, native land, reservation land, cut-off land, comprehensive land claims; you’re looking at municipal, provincial, and federal parks. So in terms of, where I am culturally, dealing with the ramifications of making a ‘landscape’, you know, it becomes a very complicated process of the perception of what you’re trying to say within the landscape concept.

On settling land claims:

It’s an extinguishment policy. If you’re going to settle a land claim with this province […] your rights will be extinguished forever. And if everything is forever, I have to count how much raindrops fall on my traditional territory for a year. They’re not free. I’m not just going to give you a rainbow for nothing. I’m not just going to give you an Indian Summer climate for free. You’re going to have to pay for it. This is what natives have to deal with.

Published May 2016, Westender